The Council for West Virginia

Archaeology reproduces these original ogham (ogam) petroglyph articles for the

record only. We give absolutely no credence to their conclusions.

For articles discussing these claims, see the listing at the end of this page.

Part 2

LIGHT DAWNS ON WEST VIRGINIA HISTORY

By Ida Jane Gallagher

© 1983 WV Division of Natural Resources, used with permission

On an eventful November day in 1982, Robert Pyle, Tony Shields, Arnout Hyde Jr. and Ida Jane Gallagher visited the Wyoming County Petroglyph. They were joined by pilot Edward Helm, who assists Hyde with aerial photography; student pilot Claudia Kingsbury; and Gallagher's father, H. P. "Friday" Meadows, who provided four-wheel drive transportation.

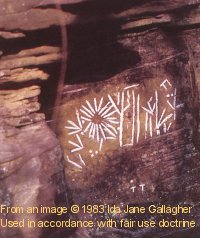

The group scrambled up a steep bank to the rock ledge. A blaze of autumn leaves almost concealed the narrow shelter which lies recessed beneath a cliff overhang. Gallagher's first look at the stunning ten-foot-long petroglyph assured her that it was of major historic value.

|

Robert L. Pyle and Ida Jane Gallagher mark cloth

using Pyle's newly developed method of recording petroglyphs.

Credit: Arnout Hyde, Jr.

|

Camera shutters clicked repeatedly. Pyle and Gallagher collaborated on the recording. They agreed upon which of the rounded, weathered grooves were the original work and chalked them for clear photographing. This was a decisive step, because graffiti added over the centuries of natural cracks in the rock are hard to distinguish from the original incised markings when photographed or transferred to a latex peel. They took more photographs. Again, thin white fabric was stretched across the panel, and the chalked markings were recorded with a permanent ink felt pen.

The sun figure on the petroglyph and the southeasterly orientation of the site made Gallagher wonder if the winter solstice sunrise might be observed from the rock shelter. The winter solstice occurs on the shortest day of the year. December 21-22. Ancient sun-worshipping people held important winter festivals on this day. As the days grew shorter, they feared that the disappearing sun would leave them to die. They appeased the sun god by making blood sacrifices, building huge bonfires, and practicing other superstitious rites. As the days lengthened, they celebrated the sun god's return.

The intriguing prospect that a winter solstice sunrise might be connected with the petroglyph added a new facet to what Gallagher had already surmised: the rock carving was created for a specific reason by someone acting under a cultural influence previously unidentified in West Virginia.

As soon as possible, she contacted Dr. Barry Fell, America's leading decipherer of ancient inscriptions. He agreed to undertake the decipherment. Hyde forwarded clear photographs and Gallagher sent the tracings that she and Pyle had made.

Fell's enthusiasm matched Gallagher's when he saw the material. He immediately identified the script called Celtic Ogam, for it is one of the ancient scripts that he encounters regularly on American stone carvings. He translated the Celtic Ogam into the Old Irish language. Next, he translated the original Old Irish into modern English. According to Fell, the Wyoming County Petroglyph bears this astounding message:

"At the time of sunrise a ray grazes the notch on the left side on Christmas Day. A Feast-day of the Church, the first season of the (Christian) year. The season of the Blessed Advent of the Savior, Lord Christ (Salvatoris Domini Christi). Behold, he is born of Mary. a woman."

Before team members recovered from the impact of this astounding translation,

Fell reported his decipherment of the script on the left side panel and a brief

Algonquian (Amerindian language) text that is inserted in the "turkey track"

area above the right section of the main panel. The Algonquian says, "Glad

Tidings."

The small left side panel and several carefully inserted markings on the main panel are in a third script called Tifinag. Fell thinks this is a later addition to the petroglyph. The Tifinag gives this instruction:

"Information for regulating the calendar by observing the reversal of the

sun's course." (By reversal is meant the winter solstice, when the sun turns

back toward the north after reaching its maximum point in the southeast.)

Fell explains that Tifinag is a Scandinavian Bronze Age script that linguists have identified in Canada, Great Britain and Libya and North Africa. He suggests that Norse seafarers were responsible for the widespread use of the script. The Tifinag on the rock shelter carvings translates into the North African Berber (Libyan) language. Apparently, the blonde Tuareg Berbers preserved the ancient Tifinag alphabet as well as the physical traits of the Norse, who traded with the Berbers and settled in North Africa. Fell's detailed decipherment and comments about the implications of his translation follow this article.

Fell pointed out that team members could verify his decipherment by observing the winter solstice sunrise from the Wyoming County Petroglyph. This statement set off a chain reaction.

Team members had speculated that the petroglyph design that looks like two mountains with a gap between them was a visual clue that the sun would actually rise in a horizon notch. In addition, Fell's preliminary decipherment of the crisscross lines on the figure read, "notch."

But, compass readings did not bear this theory out. Using astronomical tables, the team corrected for local conditions (latitude, elevation, time period, etc.) and estimated that the sunrise point was about 139 degrees. This was nowhere near a gap in the mountains. They wondered what, if anything, the rising sun would have in store for them.

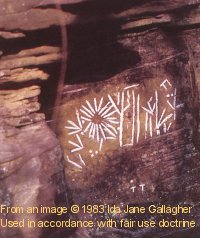

First glitter of sunlight strikes left side of petroglyph at sunrise.

Credit: Cropped from a larger copyrighted image by Ida Jane Gallagher.

|

Icicles clung to the overhanging rocks when Tony Shields, Ida Jane Gallagher, H. P. Meadows and Bradley Toler met at the Wyoming County Petroglyph before sunrise on December 22, 1982. A light covering of snow brightened the clear morning. Shields watched impatiently as shadows moved down the tree trunks on the mountain above the rock shelter and the horizon lightened. At last, the first glimpse of the sun broke over the mountain ridge at 9:05 A.M.

Gallagher began photographing a spectacular sunburst, not realizing until the film was processed that the rising sun looked like a six-pointed Christmas Star. Shields made compass readings and kept an eye on the petroglyph to see where the sun's direct rays would strike it.

"Look! Look! It's (the sun's rays) hitting the panel," he called. A glimmer of pale sunlight struck the sun symbol on the left side of the petroglyph, and the rising sun soon bathed the entire panel in warm sunlight. Shields immediately noticed that the sunlight was funneling through a three-sided notch formed by the rock overhang, the upper left-hand wall of the shelter and a rock shelf that jutted out above the small petroglyph on the lower left wall. A shadow cast by the left wall of the shelter fell to the left of the sun symbol and its adjacent markings. As the group watched, the shadow inched from left to right. Before their eves, light dawned on West Virginia history.

"That proves it," Shields said pointing to the wall notch. He was the first to realize that Dr. Fell's decipherment never mentioned the horizon. It specified only that a ray of sun would graze the notch on the left side. The ancient scribe was referring to the shelter wall notch!

This most remarkable turn of events served as a reminder that things do not always happen as expected. The group continued to watch as the solar phenomenon demonstrated physical proof of Fell's decipherment.

How appropriate it is that this ancient testament to Christ's birth was carved in the West Virginia hills where mountain folks have deep religious roots.

Early Christians connected Christ's birth with the winter solstice. The Gospels do not specify the day of Nativity. However, in the fourth century A.D. the church fathers set December 25 as the date in order to incorporate the pagan winter festivals of rebirth in the Christian tradition.

Julius Caesar reformed the calendar in 46 B.C., and it was used by Europeans until the 16th century (American colonies adopted our present-day calendar, the Gregorian, in 1752). December 25 was the winter solstice date in the Julian calendar. Caesar intended to begin the New Year on December 25, the Roman feast of Saturnalia, but due to an unfavorable waning moon, he put it off until January 1. Thus, between the fourth and 16th centuries, Christmas Day and the winter solstice both fell on December 25. This explains why the winter solstice sunrise was viewed by the author of the ancient message at the Wyoming County site on Christmas day instead of December 21-22 in the Julian dating system.

When Fell heard the news of the winter solstice sunrise, he was greatly encouraged. He had deciphered a similar petroglyph in a Texas cave shelter that gave instructions for determining the equinox (equal days and nights). A research team was present to watch the sun validate that decipherment on the fall equinox, September 22, 1982.

Because of the Christian content of the Wyoming County Petroglyph, Fell checked

old Celtic Bibles where he found exact words and phrases used in the translation.

He also made a study of Chi Rho symbols, which are the Greek letters for the name,

Christ. They appear in numerous forms in manuscripts and on items associated with

the practice of Christianity He discovered that three Celtic Chi Rho's appear

on the Wyoming County Petroglyph. One is the mountain-like symbol that had been

such an enigma to the team. The three Celtic Chi Rho's enabled Fell to give a

range of possible dates for if petroglyph, which is between the sixth and eighth

century A.D.

One can only speculate about who inscribed the Wyoming County Petroglyph until researchers accumulate more evidence. West Virginians may never know whether an Irishman, a Berber, an Amerindian or all three made the carvings. But the undeniable fact is that the petroglyph is there, and its decipherment is validated by a natural phenomenon. Ancient history however, has a few insights to contribute to this puzzle.

Irish monks possibly reached North America by the sixth century A.D. St. Patrick Christianized the Irish between 432 and 461. By this time the Gaelic people had established a class of learned men, who found a natural place in the Christian establishment. A century after St. Patrick's arrival, Irish monks and scholars began evangelizing abroad. St. Brendan, an Irish monk, supposedly made a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean from Ireland to Newfoundland on the eastern coast of Canada in the sixth century In modern times Timothy Severin set out to duplicate St. Brendan's voyage in a leather-hulled sailing boat, built to sixth century specifications. His successful voyage which proved the trip was possible, was reported by National Geographic in December 1977.

The question that American historians never have answered satisfactorily is WHO

were the Amerindians? History books gloss over the fact that Americans have an

ancient past. European explorers and settlers observed during America's colonial

period that native Americans represented a variety of racial stocks and had developed

an amazing range of culture from complex urban societies to primitive family units.

But the most striking difference was the number of spoken languages. Ethnologists

later estimated that more than 50 unrelated linguistic (language) stocks and 700

distinct dialects were spoken north of Mexico! The linguistic stocks had no common

vocabulary or grammatical structure.

This suggests that successive groups of immigrants reached America, beginning

in a distant time when hunters crossed the Bering land bridge between Siberia

and Alaska and still continuing today. A growing body of convincing information

points to an active period of trans-Atlantic crossings beginning about 2500 years

ago; these waves of immigrants were absorbed into the American melting pot along

with their customs and languages.

The linguistic evidence that foreign people reached our shores has been preserved

on petroglyphs. These stone carvings mark the beginnings of America's historic

period. Because they can be deciphered by Fell and others, Americans are discovering

that they have an ancient history. Viewed in this context, is it really so strange

to find Old Irish and North African inscriptions on the same stone carving that

bears American Indian (Algonquian) "turkey tracks"?

INVESTIGATIVE TEAM VISITS A BOONE COUNTY PETROGLYPH

|

Horse Creek Petroglyph in Boone County before it was chalked.

Credit: Arnout Hyde, Jr.

|

Shortly after the investigative team visited the Wyoming County Petroglyph, Helm learned of another one in Boone County, from local residents Jerry and Steve Stone. The Stone brothers made arrangements with the land owner for a group of investigators to visit the rock carvings, which are named the Horse Creek Petroglyph.

On the drizzly afternoon of December 20, 1982, the Stones met Arnout Hyde Jr., Claudia Kingsbury and Ida Jane Gallagher and led them to the site. The group slid down a muddy creek bank to reach a rocky outcrop that holds a series of petroglyphs. When they peered into a low rock shelter, they saw a lengthy series of markings gouged into the rear wall. Gallagher thought that they were the same Celtic Ogam script that the recording team encountered on the Wyoming County Petroglyph. Crouched under the rock ledge -- which all agreed was a perfect spot for snakes in warmer weather -- they took turns removing silt deposited by creek flooding from the surface of the carvings.

As they took photographs, the rain turned to spitting snow. Further removal of debris and silt, which was necessary for making a permanent recording, was abandoned for a better day. Fortunately, they were able to make clear photographs. These were sent to Fell, and he immediately began decipherment of the lengthy inscription. His translation of the Horse Creek Petroglyph further validated the Wyoming County Petroglyph's inscription.

Fell called the Horse Creek Petroglyph, "a sensational find." He believes that it may be the world's longest Ogam stone carving. It also contains a second script, a short Libyan addition to the original work. Fell dates the Celtic Ogam from the same period (sixth to eighth century) as the Wyoming Petroglyph. The Horse Creek carvings also translate into the Old Irish language. The complete decipherment is given and explained in Fell's article.

The main part of the long inscription of the Horse Creek Petroglyph is written in three horizontal lines. The reading begins with the middle line (see Fell's decipherment) and is translated as follows:

Line 1 (middle) "A happy season is Christmas, a time of joy and goodwill to all people.

Line 2 (bottom) "A virgin was with child; God ordained her to conceive and be fruitful. Ah, Behold, a miracle!"

Line 3 (top) "She gave birth to a son in a cave. The name of the cave was the Cave of Bethlehem. His foster-father gave him the name Jesus, the Christ, Alpha and Omega. Festive season of prayer."

The far left portion of the inscription surrounding the hand translates: "The right hand of God is a shield. -- a prayer."

Beneath it on the left is the short Libyan script that says: "The right hand of God."

To the left of this inscription is another petroglyph that bears a partially encircled hand. It appears as a rebus, a type of riddle in which words and phrases are spelled out in the form of the object whose name they represent. Fell says that this represents the Hand of God (Dextera Dei, in Latin). He translates it, "Father, Son, Holy Spirit, One God." The Ogam letter "L" is found at the end of this and other inscriptions, which Fell reads "ele," meaning "prayer."

The decipherment of the Wyoming County and Horse Creek Petroglyphs represents a new concept of West Virginia's ancient history. It indicates that people from various cultures were here, and the clues that they left behind will continue to undergo intense study

Ida Jane Gallagher, a Beckley native, is a freelance writer who has been researching and writing about ancient American history since 1977. She does much of the field exploration and photography for her research topics.

Gallagher earned Bachelor of Science and Master of Arts degrees from West Virginia University. She has worked as a journalist and as a teacher of journalism, English and American history She lectures to historical societies and school groups. She is an active member of Early Sites Research Society (archaeological), New England Antiquities Research Association (historic research, field exploration), and The Epigraphic Society, an international organization that studies ancient scripts.

West Virginia Archeologist:

Hunter Lesser on cult archaeology

West Virginia Archeologist:

Oppenheimer and Wirtz look at Fell's methodology

Wonderful West Virginia: Robert

L. Pyle on pre-Columbian contacts

West Virginia Archeologist:

Hunter Lesser looks for pseudoscience, and finds it

Wonderful West Virginia:

Ida Jane Gallagher finds a "solstice alignment"

West Virginia Archeologist:

Roger Wise looks for that "solstice alignment" again

Wonderful West Virginia:

Barry Fell deciphers Christian messages

A second opinion:

A very different

translation of Horse Creek

West Virginia Archeologist: Janet Brashler looks for all possible explanations,

and tests them