|

|

|

Hamlinton Petroglyph in Northern West Virginia. [sic, probably meaning Hamilton Farm] Credit: Robert L. Pyle |

Petroglyph at Holbrook, Arizona. Credit: Robert L. Pyle |

© 1983 WV Division of Natural Resources, used with permission

|

|

|

Hamlinton Petroglyph in Northern West Virginia. [sic, probably meaning Hamilton Farm] Credit: Robert L. Pyle |

Petroglyph at Holbrook, Arizona. Credit: Robert L. Pyle |

|

|

The seven-inch long, black limestone Decalogue Tablet

was found in a spheroidal box of light brown, calcareous sandstone, with a whitish

cement at the edges in a small mound near Newark, Ohio, in 1860. Translation of

its Hebrew inscription revealed a shortened version of the Ten Commandments. -- Illustration from a drawing by Hilary Grimm |

|

|

Sketch of the Grave Creek Tablet found in Moundsville Mound.

This South Iberian inscription is carved on a 1½x2-inch grayish, sandstone rock.

Drawing by Clyde Keeler

|

|

|

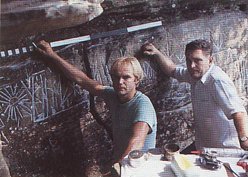

| Tony Shields with the equipment accessory

for recording the Wyoming County Petroglyph. |

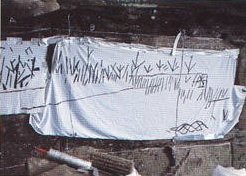

Cloth in place after being marked with

black-tip marker. |

|

|

| Tony Shields and Robert Pyle chalking out the Wyoming County Petroglyph so that it can be clearly photographed. | Latex peel held in place with poles specially

cut to length. All four photo credits to Robert L. Pyle |

|

|

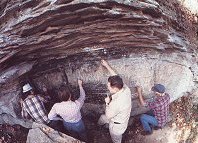

Under the direction of Robert L. Pyle (second from right), other investigative team members (left to right Ed Helm, Ida Jane Gallagher and Tony Shields chalk the Wyoming County Petroglyph. Credit: Arnout Hyde, Jr. |

CWVA Home Page |

| Controversies Page |

| "Ogham" Introduction Page |

© 2003 CWVA |