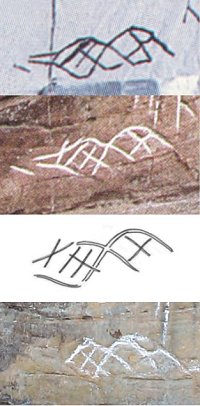

Top, Pyle's cloth tracing (1983:5)

Next, chalked by Pyle (Fell 1983:16)

Then, Fell's Figure E-8 (1983:14)

Bottom, chalked by unknown party, 2002

Photos © 1983 WV Div Natural Resources

Except bottom panel, © 2003 Roger Wise

Used with permission